- Home

- Botting, Douglas;

Gavin Maxwell Page 2

Gavin Maxwell Read online

Page 2

When Maxwell went out of the room to fetch water for the whisky I cast a quick eye over the titles in the bookcase. They were a random collection. Some were foreign editions of his own works – one about his shark-hunting venture, another about a Sicilian outlaw and bandit, a third about his travels in the Iraq marshes. Travel books by other authors rubbed covers with volumes on zoology and ornithology, works by Freud on psychoanalysis and Havelock Ellis on the psychology of sex, a book about Salvador Dali, a book by Salvador Dali, and various specialist works including an illustrated monograph on the anatomy of the female human pudenda and a police textbook on forensic medicine and murder in all its forms. When Maxwell came back into the room he said: ‘I had to sell most of my books when I was virtually bankrupted after my shark-hunting business failed. I lost almost everything, my inheritance, the lot. This is all that’s left.’

He sat me down, poured me half a pint of Scotch, opened the drawer of an escritoire, took out a small, ivory-handled pistol and without a word clapped it to my right temple and pulled the trigger.

‘You blinked!’ he cried, laying the pistol down. ‘You’re quite obviously not a born killer.’

The pistol, a .32 Colt semi-automatic engraved with his name, had been a gift from the Norwegian Resistance when he was in Special Forces during the war. This and the other implements of death in the room contrasted oddly with the animals that lived there.

‘I’ve always kept animals,’ Maxwell told me as he fed a live locust (specially delivered from Harrods’ pet department) to the monitor lizard. ‘Till this spring I had an otter I’d brought back from the Iraq marshes. Then it was killed by a roadmender in Scotland. I had a ring-tailed lemur as well until recently. But one day it bit me through my tibial artery and I nearly bled to death. I lost two pints of blood all over the floor before I got a tourniquet on to stop the flow.’

Maxwell, I soon discovered, was more accident-prone than any human being I had met. He was for ever being wrapped round lamp-posts, shipwrecked on reefs, attacked by wild animals, half blinded by sandstorms, struck low by diseases unknown to science, robbed by Arabs, cheated by crooks, betrayed by friends. In fact, in almost every way he was quite unlike any other person I had ever encountered. He lived alone and was an avowed neurotic. He chain-smoked and was rarely without an enormous glass of well-watered whisky in his hand. He was far fiercer than I had expected of an author whom a reviewer had described as ‘a man of action who writes like a poet’. Of medium height and wiry build, he held himself taut and erect as if squaring up to an imminent assault. His look was fierce and his speech, too, was fiercely authoritative, even aggressive, with great emphasis on amplifier words like ‘fantastic’ and ‘absolutely’, and sudden dramatic shifts from humour and laughter to anger and depressive gloom.

His conversation was original and wide-ranging and his personality highly engaging. He was clearly endowed with considerable physical and nervous energy, a keen analytical intelligence, boundless curiosity and a restless creative drive, the masterwork of which was the high drama of his own chaotic life – for he existed, as far as I could see, in a whirl of wild hopes and plans and tragic episodes largely of his own creating.

This whirl of high drama tended to involve anyone who happened to be in the vicinity. When I casually told him that an Oxford friend of mine who had joined the Foreign Office (and was later to become Governor of Hong Kong) had recently asked me if I was interested in applying for the job of private tutor to the Crown Prince of Nepal, Gavin’s instantaneous and exaggerated histrionics knew no bounds. ‘That job cannot possibly be what it seems!’ he pronounced, looking gravely alarmed. ‘If I were you I wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole. Were you given a telephone number to ring?’ I gave him the number of an office in Whitehall. Gavin looked at it and whistled through his teeth. ‘I thought as much,’ he said. ‘Do you have the extension?’ I gave him that too. Gavin picked up the phone and dialled the number. When it answered he gave me a conspiratorial confirming wink and brusquely asked the operator for the extension. When the extension answered he slammed the phone down as if he had just received an electric shock and shouted across the room: ‘Just what I thought! If you go after that job in Kathmandu you’ll be getting into deeper water than you ever dreamed of. It’s up to you, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.’ Only much later, when I had got the measure of Gavin’s propensity to conjure drama and danger out of thin air, did I realise that the course of my life had been shunted from one branch line to another.

Gavin was the first real writer I had ever met, and he shared my own enthusiasm for travel and wild places. It was this which had led me to contact him. In my last year at Oxford I was Chairman of the Oxford University Exploration Club, and was looking for interesting guest speakers who differed from the explorer stereotypes – the burly, booted pemmican-eaters and craggy, glacial crampon men. One Sunday in November 1957 I read in the Sunday Times a long, highly favourable review of a book called A Reed Shaken by the Wind, by a writer I had not heard of before called Gavin Maxwell, about a journey through the Tigris marshes with the renowned Arabian explorer Wilfred Thesiger. ‘As the title suggests,’ the review began, ‘he is a man on a quest; and he even gives us a hint that this is a voyage d’oubli … The moving quality of the prose is the expression of a sensibility delicate and troubled, humorous and observant, with which it is a pleasure to converse and which overlays a tough and stoical core. For such disturbed personalities the marshes become a symbol …’ I read the book, was impressed by the brilliance of the narrative and intrigued by the enigmatic persona of the writer, and wrote at once inviting him to come to Oxford to lecture about his travels.

Maxwell replied by telephone. Was I, he demanded sternly, the Douglas Botting who had just returned from an expedition to Socotra (an unexplored island in the Arabian Sea)? I said I was. ‘Have you written a book about it?’ he asked. I said I had. ‘Then I’d like to have a look at it, if it’s all the same with you.’ I brought the manuscript on my first visit to Maxwell’s flat. Later he wrote me a note: ‘Let me say at once that you are a born writer in the true sense and will be wasting your time in the future doing anything else.’ So the die was cast.

Maxwell’s lecture to the University Exploration Club at St Edmund Hall was captivating and often hilarious. At dinner afterwards we were joined by my predecessor as Chairman of the Club, a rugged ex-Marine Commando whose nose had been broken in a bottle fight in a Maltese dockside bar, and who now appeared wearing a Stetson and despatch rider’s boots and a heavily plastered arm in a sling. It was clear that Maxwell warmed to this kind of company, and when my friend told him he had broken his arm in Somaliland while trying a high-speed turn on a racing camel, Maxwell leaned across to me and whispered, ‘Now that’s what I call a real explorer.’ By the time coffee came Maxwell had formed an idea. ‘Why don’t I go on a dangerous expedition and get lost,’ he suggested to me, ‘and you come out and look for me? If you find me I can write a book about the journey. But if you don’t find me you can write a book about the search.’

He was only half joking, and when I next met him he had developed the idea. We should pool our talents and organise a major expedition – through the Berber country of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, for example, or among the Nilotic tribes of the Sudd in the southern Sudan. It was clear that he saw his contact with the Exploration Club, and myself in particular, as a means of making use of our practical knowledge and expertise in mounting expeditions to far-away places for his own purposes. The success of his book on the Iraq marshes meant he was virtually bound to be commissioned to write another travel book, but he was not himself a very practical person, and was not entirely clear how to set up complicated forays of this sort on his own account. Perhaps I could help, he suggested; perhaps I could even make the film of the expedition while he wrote the book. But first, perhaps, I might like to accompany him on a less ambitious journey.

‘I’ve got a little lighthouse-keeper’s cottage by the

sea up in the Scottish Highlands,’ he told me. ‘I haven’t been there for a year. Not since my otter Mijbil was killed. I couldn’t bear to go back alone. You’d enjoy it. It’s miles from anywhere and you could bring your textbooks.’ So began my association with that loveliest and most tragic of Shangri-Las – the tiny wilderness that was to become renowned throughout the world as Camusfeàrna, the Bay of Alders.

We drove up in Gavin’s vintage Bentley roadster at the start of my Easter vacation of 1958. There were no motorways then and it took two long days to reach the West Highland coast. Little by little as the miles sped by I began to learn more about the curiously dramatic personality at the wheel. He drove sensationally fast, like a racing driver, with much squealing of tyres and restless changing up and down through the gears. When I commented on this he told me he had once been an amateur racing driver – but only when he was crossed in love, he said, and only after he had downed half a bottle of Scotch before the start, ‘Otherwise I’d have been scared out of my wits!’ He told me the psychologist and writer Elias Canetti (who later won the Nobel Prize for Literature) once remonstrated with him for his reckless speeding. ‘“Givin, Givin,”’ Gavin said, gleefully mimicking Canetti’s pronounced Central European accent, ‘“do you really have to identify with a motor car in this way? I mean, when the car goes fast, do you feel fast? When it goes slow, do you feel slow? When it breaks down, do you feel broken down?” And I told him: “Yes, all those things.”’

At Scotch Corner Gavin pulled in for a fill-up of petrol and whisky. When I told him I would prefer a beer he remonstrated with me. ‘My dear Douglas, you can’t possibly drink that plebeian stuff. You must have a whisky!’ All games except chess and canasta were also plebeian in the Gavin canon, I discovered. It was not until we reached Northumberland and turned off the main road to the small coastal town of Alnwick that I discovered why.

‘I thought I’d show you my grandfather’s house,’ he explained. ‘It’s only just down the road.’

We roared up to the great gates of a medieval stone pile with curtain walls and battlements and round towers and a great keep. This was Alnwick Castle, the ancestral home of the Dukes of Northumberland.

‘I used to stay here when I was little,’ Gavin told me. ‘I didn’t like it much. I once said to my mother: “When are we going to get out of this tight place?” She was the daughter of the Duke of Northumberland. This was his castle – my grandfather’s castle, the seventh Duke’s. Now it’s my uncle’s, the ninth Duke’s.’

By and large, Gavin wore his exalted status lightly – though he could make use of it if he chose to pull rank or impress, or if an accent or a social mannerism pained him. Though he was born an aristocrat, his political leanings at the time I first met him were towards the more radical left. He was much preoccupied with furthering social reform among the Sicilian poor, and even appeared on the same public platforms as such committed left-wingers as Victor Gollancz, the socialist publisher, and Fenner Brockway, the radical Labour M.P. But he was a snob of a particular kind. He could not abide fools, and loathed the human pack and all herd-like behaviour. He was not a true loner, but he hated groups and could never have travelled on an expedition comprising more than two people.

We crossed into Scotland and stopped over in Edinburgh. Gavin had a commission from an industrial journal called Steel to do a photo-feature on a magnificent brand-new steel bridge across the Firth of Forth. But the journal’s editor had been badly misinformed. Though we went up the river one way and down the river the other we could find no such structure – it had not even been started. Rather than leave empty-handed we decided to photograph the old nineteenth-century bridge over the Forth, and spent a perilous afternoon clambering precariously over its ageing girders high above the swirling river. Not until we spotted policemen climbing after us among the girders of the bridge’s intricate tracery of ochre-red ironwork, and heard them hailing us to come down, did we descend to earth again.

At dinner in the grand old North British Hotel that evening Gavin was highly elated about this escapade, but as the meal progressed and the wine flowed his mood darkened, and when a band started playing and couples began to dance his mood grew positively black and he sat staring furiously ahead of him with his hands clenched together under his chin in a characteristic gesture of outrage. Was it the fact that men and women were dancing together that so affronted him, participating together in a collective tribal ritual such as he, a lifelong and irremediable outsider, could never join? Or was it simply the drink?

‘Douglas, one thing you must understand,’ he confessed over another double whisky, ‘I am no saint.’ He was, it seemed, a homosexual, though not entirely so, for women had featured in his life from time to time. It took me a few moments to take this in. There was clearly no question that the implications of this revelation could involve me in any way, but it was obviously crucial to an understanding of his complex and rebellious nature and the alienation which characterised his life. Though he enjoyed female company, and had loved several women in his time, his inclinations were more strongly Grecian in nature, he explained, and he was romantically in love with youth and beauty. ‘More Death in Venice than Antony and Cleopatra, if you see what I mean. You may not approve. But you’ll have to accept me for what I am.’ What he was, as I gradually discovered, was a troubled and tempestuous but often hilarious terrier of a man, a flawed genius whose obvious faults of character were redeemed by a rare generosity of spirit, an undimmed utopian vision of life and nature, and a stoical courage that was undaunted even in the face of ultimate adversity.

Gavin took the slow road to Sandaig. We thundered along a narrow twisting track that wound between mountains and over moorland to the west coast and the haunts of his wartime and sharking days – Arisaig, Morar, Mallaig. On the way we stopped at the houses of old friends and relatives, ex-commandos and harpoon-gunners, taking a wee dram here and a wee dram there, till the drams put end to end must have occupied the best part of a bottle and the road seemed to grow more tortuous than ever. Fortunately it ended at Mallaig, the brash, bustling, frontier-style West Highland fishing port that had been Gavin’s sharking base in the post-war years. From here, on a wild wet morning in early April 1958, we set sail aboard the island steamer bound for the Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides. I had never been this far north in Britain before, and the sights and sounds of this wild corner of Scotland were like a foreign land to me. Though Gavin had travelled these parts time and again in previous years, his enthusiasm was unabated. He was an ideal travelling companion, informed, inquisitive, even rapturous about the wild world that encircled us.

After an hour or two of butting the heavy Atlantic swell the steamer drew in beneath a great, hump-backed island called Rhum, where Gavin had hunted the basking shark a decade before. On such a storm-tossed day the impression of Rhum from the sea was daunting. Huge cliffs girt the island’s wild coast; volcanic mountains, pyramidal and black, rose straight from the sea; an extraordinary turreted Gothic edifice, an incongruous dark sandstone red in colour, stood four-square on the shore. As the ship hove-to – Rhum was still privately owned then and we were forbidden to land – a flurry of gannets hurtled around us like flying crucifixes and floating ‘rafts’ of Manx shearwaters rose and fell in the sea like flotsam. Gavin had a fund of knowledge, historical and zoological, about the island. By Rhum, and its black peaks, Norse names and oceanic birds, by this whirl of sea and weather and far and ever-changing horizons, I was spellbound, as Gavin himself had been years before. Then the ship’s siren echoed between the crags, the anchor was hauled in and the steamer pointed north-west into a heaving, rainswept sea.

We disembarked at Canna, the most westerly and most beautiful of the Small Isles. The laird of Canna, the scholar and naturalist John Lorne Campbell (an etymologist and collector of Gaelic folk lore and a dedicated lepidopterist who tagged migrating butterflies like birds), was an old friend of Gavin’s, and it was at his home, Canna House, a comfortable old man

sion overlooking the harbour approaches, that we stayed during our few days on the island. It was on Canna that Gavin’s mind began to turn to the subject of his next book. During a long walk along the high cliff’s edge of grassy, rabbity Compass Hill in a blustering gale he argued the pros and cons of the various alternatives. One was a biography of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the mad black tyrant-emperor of eighteenth-century Haiti. I thought this an interesting but rather arcane topic. The other possibility, Gavin told me between booming gusts of wind, was a book about his West Highland home at Sandaig, our ultimate destination. ‘I’ve written a little outline about it. Perhaps you’d like to read it when we get back and tell me what you think.’

The thousand-word document was not so much an outline as a sample of text. I remember it as one of the most brilliantly written evocations of place I have ever read, conjuring up in a few lines a magic world of light and sky and water, an enchanted patch of earth and the miraculous grace and freedom of the wild creatures that inhabited it. It described an unforgettable episode of natural prodigality and death Gavin had observed on a late summer evening in Sandaig Bay some five years previously. The twin sons of the local peat-digger had brought a bulky packet of letters down to Gavin’s house by the sea, and he was reading the letters in the twilit kitchen when he heard the boys shouting from the shore.

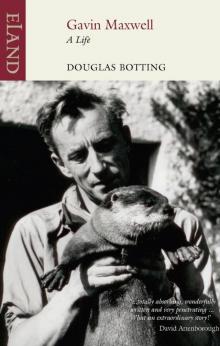

Gavin Maxwell

Gavin Maxwell